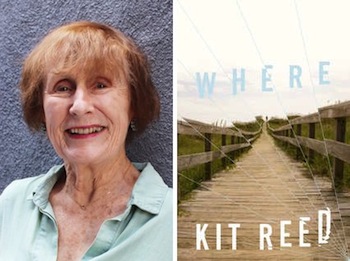

Recently, friends and Tor authors Kit Reed and Max Gladstone sat down to discuss Kit’s new novel, Where. Based around the sudden and enigmatic disappearance of an entire coastal town on the Outer Banks of Carolina, Where was inspired by mysteries like the ghost ship Mary Celeste and the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island.

Kit and Max, whose Craft Sequence novel Last First Snow arrives from Tor Books in July, talked about the connection between fiction and mysticism, why authors tend to read in the genre they write, and conversations that books have amongst themselves.

Max Gladstone: What’s the seed of Where? (If there was a seed?) If so, did the book grow and twist out of the seed, or is the seed still there inside?

Kit Reed: Probably the seed is the story of the mysterious ghost ship, Mary Celeste. Dead empty, nothing disturbed. Where did they all go? I read about it when I was maybe 12, in a book called The Sea Devil’s Fo’csle, and I read it over and over and OVER again. The idea that people could just VANISH…

MG: I often feel like my books are in conversation with one another—that one book’s knocking on another’s door, or recoiling in horror from another’s premise. Does that ever happen to you? Is Where in conversation with books of yours, or with other folks’ books, or with something else entirely?

KR: Where is probably in conversation with nothing I ever wrote and everything I ever wrote, And nothing I’ve ever read and everything I’ve ever read.

MG: There’s an alchemical stage to good writing, I think—where concepts germinate and recombine in the brain without the author’s conscious input. I grow cautious when I’m researching a project too close to writing it, get worried that I’ll decide what’s important about the material before the material really has time to work on me. Though maybe that’s a bit too mystical.

KR: What we do is a mystery, those of us who just “make it up as we go along,” as a venerable academic told me. “Mystical” makes me think we may have come from the same planet.

MG: It’s a fun planet! You read fiction, primarily?

KR: I do. And—weird; I read after I’m done for the day: I need to get lost in somebody else’s novel—one that’s completely unrelated to the story I’m trying to tell. Brain’s set on PARK, but subconscious isn’t. Suddenly it goes rmm rmm rmmm, takes off and comes back with something I didn’t know about what I’m doing. I love seeing other writers’ narrative tactics—how they got me into the tent and how they keep me inside the tent. How the story puts itself together. I read for character—what they think and do, what they say to each other and what happens to them in the end. Imagined lives. Yeah, with a few diversions—just reviewed Brad Gooch’s amazing memoir—I can’t stop devouring fiction. Notable poet friend Richard Wilbur explained it all for me way back in the day, when I gave him a copy of my third novel. “We tend to read what we write.”

While we’re at it, where does your fiction come from?

MG: All over the place—though recently I’ve thought a great deal about how, since I grew up reading a lot of fantasy and science fiction, those stories became the narrative tools I used to understand the non-physical world. So now, when I try to figure out how politics or finance functions, I reach for analogous concepts from fantasy, SF, myth, and games. For example: Three Parts Dead emerged from, among other things, a long conversation about corporate bankruptcy during which I realized the entire process made more sense if I thought about it as necromancy performed on gods of an old-school pagan sort. I tell stories to excite and interest readers, but I’m also often trying to work out the consequences of an idea myself. Does that make any sense?

KR: Absolutely. We write to make our lives make sense, as in, figuring out exactly what we’re writing about and what it probably means—trying to bring order to what is, essentially, chaos. Particularly the business of understanding the non-physical world, or trying to. WHERE is me grappling with the fact that there is a non-physical world and trying to unpack whatever drives people like me to knock themselves out dealing with what are, essentially, insoluble mysteries.

MG: What brought you to Kraven Island?

KR: I spent two years in South Carolina, one on Parris Island and one in Beaufort when I was 15 and 16. We moved again the summer I turned 17, but I can’t leave the landscape behind; it came home with me and set up housekeeping in my head. I went to Beaufort High School, famous because Pat Conroy went there back in the day. Once you’ve ridden around Beaufort and the offshore islands in some kid’s pickup truck, over the causeways and down those country roads, the territory takes you over and moves in and rearranges the furniture inside your head. For good.

MG: On a similar note, Where features three strong leads with very different voices; care to talk about their backgrounds and relationships? Why Davy, Merrill, and Ned?

KR: You mean in the story, or are you asking if I’m drawing people I know?

MG: I guess I’m asking what drew you to tell this story through those particular characters—or did the story emerge out of the characters, rather than the other way around? Or is that a false dichotomy? Which do you do?

KR: Holy cow, I don’t know. I started with the missing colony, and I knew where they came from, and then I guess Merrill told me what happened the day they got dumped in this mysterious new place. I had to hear her coming—the cadencing, what her issues were, meaning I heard everything she saw and how it affected her and what she did about it. Then I had to hammer at the thing and hammer at it until what was happening happened in her voice, at her metabolic rate. She’s there and she’s miserable and she’s looking for somebody. Owait, she has a kid brother. Owait. She’s looking for the guy she thinks she loves. Owait, her father is about to wreck their situation here, and that’s not the first time he wrecked something. OK, and he’s doing this, WHY?

That way. It came about that way. What about you?

MG: I write with a mix of planning and improvisation—often I’ll be working with a structure in mind only for new characters and situations to swan into the limelight and take over. Some of my favorite moments as a writer have come out of trying to resolve conflicts between my plan and the way the story’s chosen to surprise me.

KR: These things are full of surprises. That’s the cool part.

MG: I don’t generally draw off people I know when I build character, though. Sometimes snatches of friends will make it onto the page—but that’s more a case of finding habits or turns of phrase apposite to the character I’m building, rather than refiguring people into characters. Life’s there in my work, but it goes through a lot of alchemy before it becomes fiction. (It seems to me this is a good way to stay out of trouble, too!)

KR: Indeed! Although I know a woman who was writing a novel about Kirk Douglas and a horse trainer, don’t remember the deets but she was scared of getting sued by the Douglas family. I remember telling her it was unlikely that he’d file a suit claiming that she’d defamed him because she was making some bad thing that he did public. No way. That would be him admitting that he actually DID whatever that atrocious thing was. I spared her the news that her book would never get finished, ergo never be published.

MG: This one’s a bit of a spoiler, but tackle it if you want: in its final act, Where seems to throw down a bit of a gauntlet to readers’ hunger for clear explanations and parlor scenes in fiction, especially weird fiction. (“The aliens were really Old Man Withers all along!”)

KR: Or, “This all happened because of this mechanical thing that I am now going to explain to you in intense, technically detailed that show you just exactly HOW I got this rabbit into the capsule and what foreign elements came together in this exquisite pattern.” Sorry, man. I can’t be that person. This story told me exactly what it was doing and how it would end even before it started.

MG: I’m really interested in the notion of enduring mysteries, ranging from their simple expressions (JJ Abrams’ box) to Otto’s mysterium tremendum et fascinans. How has the tension between explanation and mystery shaped your own writing?

KR: I’m a Catholic, and we are brought up on mysteries. Knowing that there were things that you didn’t understand, the mysteries NOBODY can explain, and learning to live with them—that’s part of my life. Like what’s going on behind the curtain between the seen and the unseeable. As in, on a smaller scale, what happened to the Roanoke colony. Where the crew of the Mary Celeste went, whether they were murdered or drowned or they actually made it to some atoll and there are in fact descendents living in a colony there—there are theories on these events, and berzillion theories on the spontaneous human combustion case that sparked my novel Son of Destruction, but as to physical, scientific HARD FACTS, provable solutions, although science tries—and science fiction tries—although most people claim otherwise, there are no absolute ones.

MG: I love how that leads to the question of overlapping truths—we think of, for example, the sort of truth discovered through hard science, and the sort of truth discovered through historical research, to be identical. In a sense they are—or are they?

KR: Not really, as you demonstrate! History is subjective, seen through the eyes of the beholder; memoir is subjective, and so is the most realistic fiction because it’s filtered by the writers’ choices—which details, which words. Now, science—out of my realm, I fear, but everything is filtered through the humans engaged in whichever work. We supply meaning. A rock is just a rock until somebody bashes you with it or throws it through your window or finds one on top of a mountain and carves an emblem into it.

MG: If we went back into the past in our time machines, which of course we have, because this is the future, we’d either see someone spontaneously combust or we wouldn’t. The Mary Celeste’s crew would drown or they’d swim to safety, or something else entirely. But that wouldn’t tell us all that much about how contemporary people interpreted what they saw, or why they chose to tell the story of what they’d seen to others in quite the way they did. It wouldn’t explain what those stories meant to those who told them.

KR: Or to any given audience.

MG: Speaking of parallels with religion…

KR: Well, yes! There are things we know and things we’ll never know, and learning how to live with it is half the fun.